By Ned Benton and Judy-Lynne Peters

The State of New York maintains an opulent public art gallery including portraits that celebrate eight public officials who enslaved New York residents, not mentioning their slaveholding. The gallery is the New York Hall of Governors, and the officials are eight of our earliest governors.

The Hall of Governors gallery is not unique, as we have learned via the New York Slavery Records Index’ recent initiative to pair our searchable database of over 39,000 records with inventories of historical artwork. In this article we outline what we have found as we began adding a visual dimension to New York’s records of enslavement. We present each of the rare depictions of New York’s enslaved people themselves, and then we provide links to more than 150 paintings and statues of New York’s enslavers.

Art featuring New York enslavers appears mostly in museums and public settings, typically without acknowledgement of the individuals’ slaveholding involvement. Several institutions have excellent programs about enslavement, such as the New York Historical Society’s exhibit on Slavery in New York and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. The Worcester Art Museum has begun to identify portraits of slaveholders in their collections and to describe for museum patrons each person’s connections to slavery. This is a model we hope to see adopted by museums universally, but implementation will require access to resources like the New York Slavery Records Index.

As a rule, we do not advocate removing art from public view simply because it depicts a slaveholder. If paired with candid and accurate recognition of enslavement, museums are appropriate places for people to learn about enslavement through these artifacts. As we articulated in Slavery and the Extended Family of John Jay, any art or memorialization should acknowledge the subject’s engagement in slavery, even when recognizing or celebrating other enduring, important achievements.

By pairing of enslavement records and art, we hope to provide more complete and accurate information for communities to use as they research and revise their historical narratives, and consider whether to rename buildings and streets, relocate statues or refocus memorials.

Art Depicting Enslaved Persons

We start by presenting art featuring people who were enslaved in New York. Since there are so few, we include the images along with a summary of what is known of the person. In some cases we can provide a name from our database with certainty. With others, particularly early works, we can establish a reasonably close association with individuals.

“Family Group” by Willem C. Duyster (c. 1631-1633), courtesy of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

The above painting of a Dutch family, dated 1631-1633, comes from the period when the West India Company had colonized what is now lower Manhattan. The artist does not identify the location of the domestic scene or its subjects, a wealthy family and an enslaved person dimly lit in the background. We know, however, that the West India Company acquired people for enslavement and then, as illustrated below, assigned them to families in New Amsterdam.

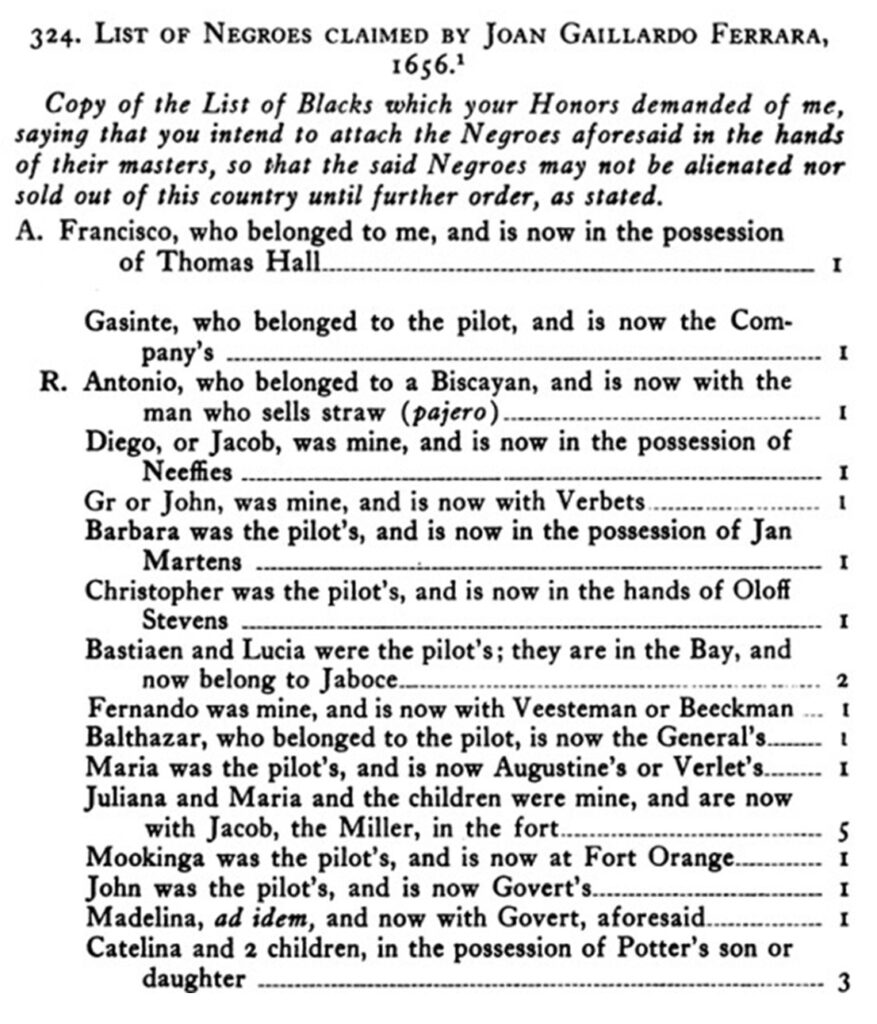

From the records of the West India Company 1656

The drawing below, from about 1642, depicts Peter Stuyvesant in New Amsterdam and a much harsher version of enslavement. Rather than the warm domestic scene with the elegantly dressed black youth depicted by Duyster, there are four enslaved people loading supplies at the harbor.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. Nieu Amsterdam.

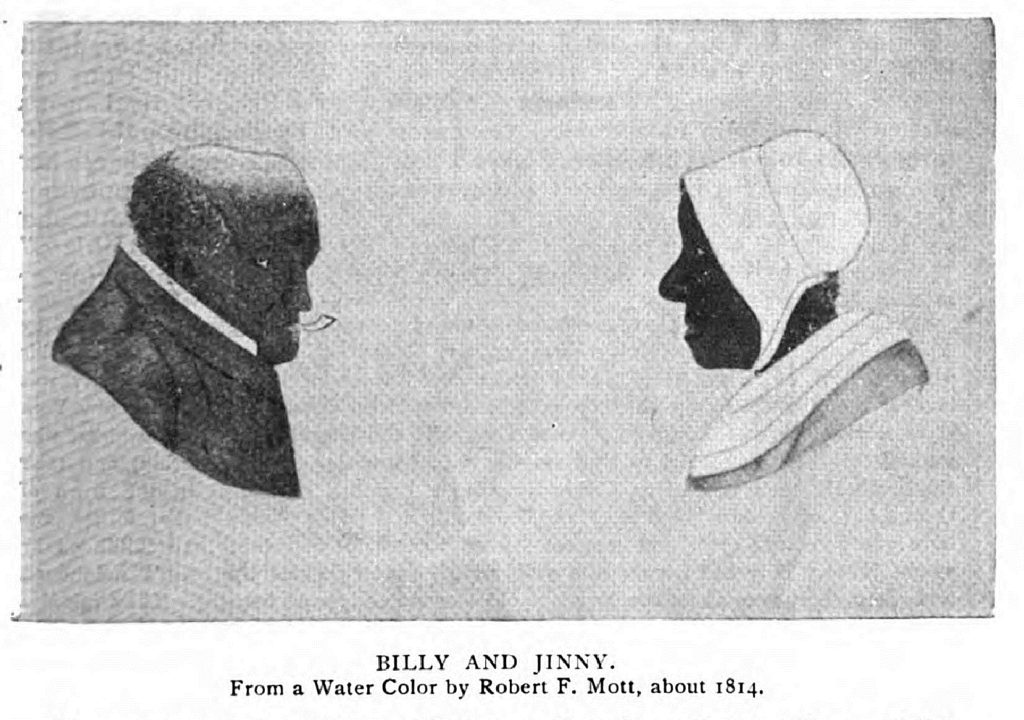

The next portrait is from a water color of “Billy and Jinny” painted around 1814 by Robert F. Mott, a member of the family which both enslaved and eventually emancipated the couple, in Mamaroneck Township, Westchester County.

Jinny arrived in New York from a slave ship in 1744 and was enslaved by Samuel Underhill on Long Island. Billy was born around 1728 to Tom and Caty, who were enslaved by Thomas Bowne, also of Long Island. At one point, Billy was acquired by a neighbor of the Underhills, but when the Underhills moved from Long Island to Mamaroneck, they traded to again acquire Billy so he and Jinny would remain together. The two were later sold to the Motts, whose Quaker religion obligated them to eventually emancipate their enslaved people.

Billy and Jinny continued to live with and work for the Motts after their emancipation. Jinny raised a large family of her own and cared for many generations of Mott children. Billy, also known as Banjo Billy, was famous for his banjo playing, his patriotism and his “hatred of all Tories,” according to the Mott family history by Thomas C. Cornell, as described in a separate NYSRI article titled Jinny and Billy of Mamaroneck.

“Boy of the Van Rensselaer Family” by John Heaton, published in Remembrance of Patria: Dutch Arts and Culture in Colonial America, 1609-1776, by Roderic H. Blackburn, Ruth Piwonka, and other writers (Albany, 1988), 318 pages,

The above portrait from the 1730s depicts a child of the Rensselaer family, along with an enslaved person in the dimly lighted background.

Caesar: A Slave, ca. 1850. Daguerreotype. New-York Historical Society

This framed photograph of Caesar was the poster image of the New York Historical Society’s 2005 exhibition on slavery in New York. Caesar’s gravestone at the Nicoll-Sill family burial ground in Bethlehem, New York says he was born in 1737 and died in 1852, which, if true, would have him outliving three slaveholders.

Peter Williams (1750-1823) Oil on canvas at the New York Historical Society.

Peter Williams was was a founding member of New York’s First Methodist Church for Negroes in 1801, formally known as the Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church. Peter Williams was born a slave in New York, and was sold by James Aymar to the Trustees of the John Street Methodist Church in 1783. Enslaved to the John Street Methodist Church, he served as sexton (janitor) of the until 1796, when he and his wife Molly, born Mary Durham (1748–1821), were emancipated by the Methodist Society. Williams subsequently operated a successful tobacconist shop on Liberty Street.

Mrs. Schuyler Burning Her Wheat Fields on the Approach of the British (1852) by Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze (Germany, Gmünd, active United States, 1816-1868), on display at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Although the above painting features the Schuyler family, at its center is an unidentified enslaved youth holding a lantern, or possibly a container of fuel.

The painting dates from 1852, long after the burning of the wheat fields (possibly a family fiction, according to museum notes), and Leutze fails to identify the youth, probably one of many enslaved people associated in our database with General Philip Schuyler (1755-1804) and his wife Catherine Van Rensselaer Schuyler. The painting also includes the Schuyler’s daughters Angelica and Elizabeth. Elizabeth eventually married Alexander Hamilton.

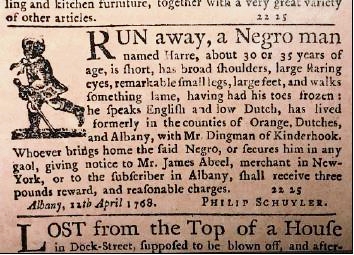

One young man enslaved by the Schuylers is Harre, who escaped from them in 1768. He was described in a runaway slave ad as walking “something lame having had his toes frozen.” What would Harre have to say about this portrait?

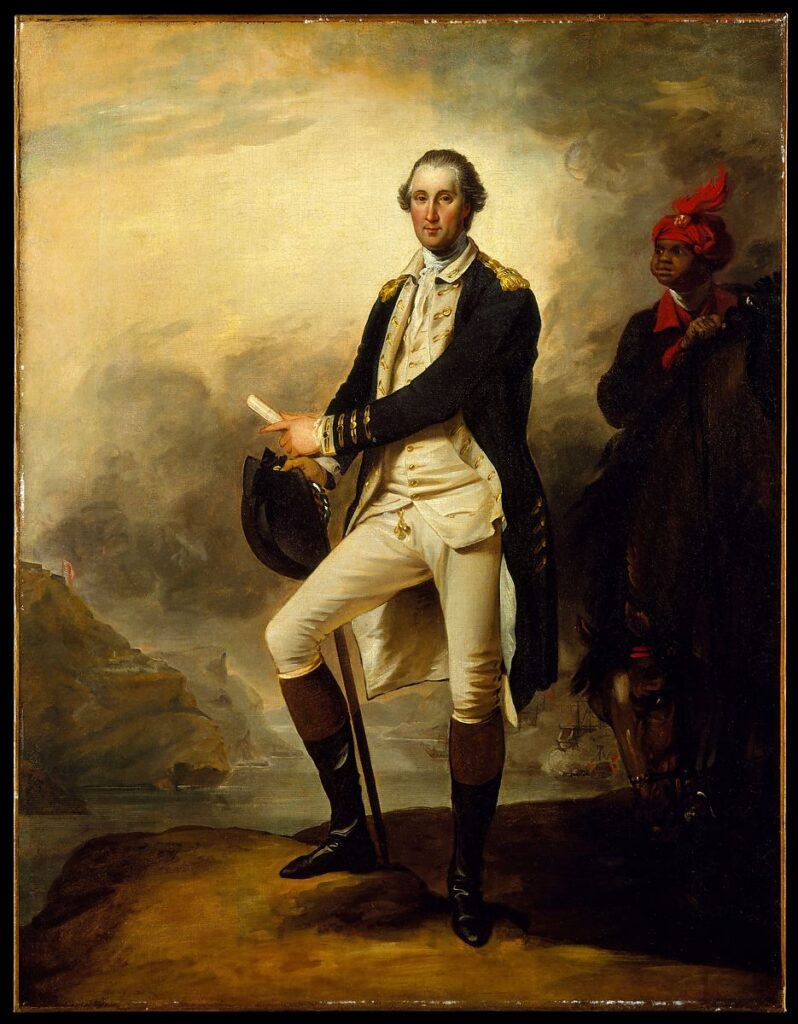

George Washington (1732–1799) standing on a bluff above the Hudson River with his enslaved personal servant, Billy Lee, on horseback behind him. Painting by John Trumbull. From the Metropolitan Museum of Art

William “Billy” Lee was one of hundreds of individuals enslaved by George Washington at Mount Vernon. However, unlike the others, he served as Washington’s personal servant, accompanying him on most of his travels for decades, including on the depicted visit to New York. In an article about William Billy Lee from the Mount Vernon estate, his duties are described as ranging from tying a ribbon in Washington’s hair to organizing the general’s voluminous papers. (We include him in this article because the painting shows him as an enslaved person in New York.)

Pierre Toussaint (ca. 1781-1853) from the New York Historical Society

Pierre Toussaint was born in slavery in Santo Domingo, Haiti, and brought to New York about 1797 by Jean Bérard, a wealthy French landowner who continued to enslave him. Eventually emancipated, Toussaint became comparatively wealthy as a hairdresser and used his wealth to emancipate many other slaves. The Catholic Church venerated him for his many acts of charity.

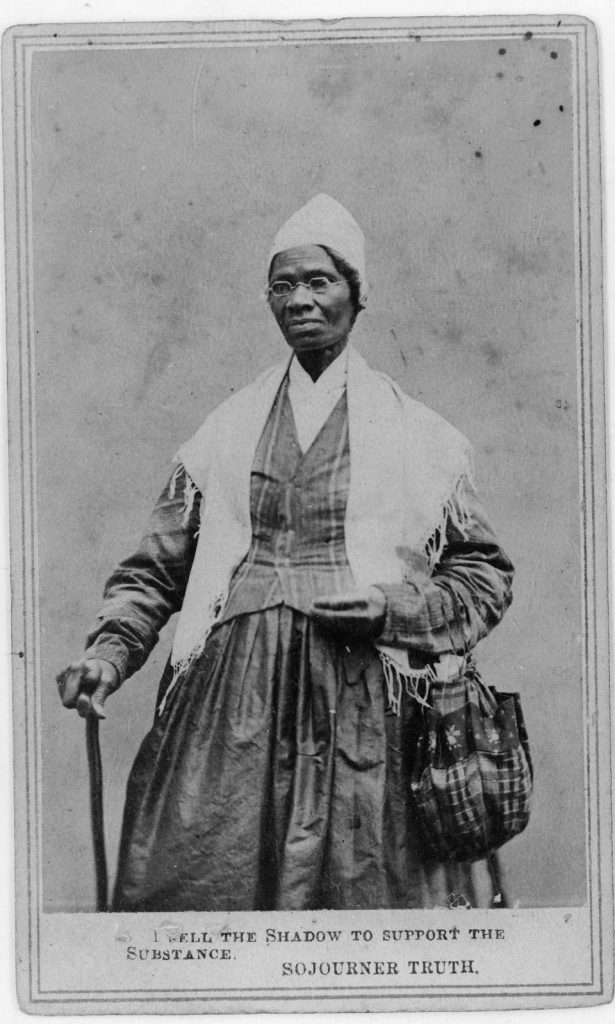

Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth, an abolitionist and advocate for women’s’ rights, was born into slavery in New York in 1797 and named Isabella Baumfree. In 1828, she was emancipated. We document many of the additional known details of her enslavement and her emancipated life in a separate article: Sojourner Truth-Identifying Her Family and Owners. The above photograph is one of many she commissioned as a way to earn income and to advocate for Black women, as discussed in The Smithsonian Magazine’s article: How Sojourner Truth Used Photography to Help End Slavery.

There are also many sculptures of Sojourner Truth at sites in New York and across the nation. These include:

- The Women’s Rights Memorial in Central Park, New York City, New York

- The Sojourner Truth Memorial Statue in Florence, Massachusetts

- The Sojourner Truth Bust at the U.S. Capitol, Washington, D.C.

- The Sojourner Truth Statue planned for the walkway over the Hudson State Historic Park in New York

- Statues in Battle Creek, Michigan where she lived later in life

- Statue at Thurgood Marshal College in San Diego, California

- Statue of Sojourner Truth as a young woman in Esopus, New York

Joseph Stewart is in the background of this 1816 watercolor of Elizabeth Cooper by George Freeman.

According to the James Fenimore Cooper Society, Joseph Stewart was known as “The Governor” and lived in Cooperstown. He was enslaved by Abraham Ten Broeck, but from 1799-1802 he was “rented” to William Cooper for $76-80 per year. Following his emancipation, he continued working for the Coopers. Thus, at the time of the above painting, he may have been a free servant.

Art Depicting Slaveholders

The vast majority of art associated with enslavement depicts the enslavers. Typically, they were wealthy, large landholders, and often military or government leaders. Many of the works are portraits painted in oil that celebrate military or public service. There are also sculptures created as cemetery or public park memorials. Our search located art held by 26 organizations, with the largest holdings by the New York Historical Society and the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.

William Bayard (1761-1826), painted in 1794 by Gilbert Stuart, from the Princeton University Art Museum. The museum’s interpretation says “Descended from an old New Jersey family, merchant William Bayard was highly regarded for his intelligence and integrity. “

Above is a not unusual example, in this case from the Princeton University Art Museum. While the museum describes his “old New Jersey family” and his “intelligence and integrity” our records show Bayard’s family to have engaged in slaveship investing, and Bayard himself reported 7 enslaved people in his household in the 1790 census, four years before the painting was created.

The following table lists more than 150 sculptures, paintings, sketches, and photographs of slaveholders from New York, though some of the artwork now resides out-of-state. The information is organized first around the works’ current location, then by name of the slaveholders, their county of residence and the unique code tracking all records associated with the enslaver. (To see these records, enter the tracking code in the SEARCH field titled “owner unique code.”) At the end of each row is a link to the database’s full record for that piece of art.

The records above are those that we have discovered thus far, from records based on only one state – New York. The list will grow as we add to our database of slavery records, and as we find more vintage portraits in colleges, town halls and historical sites across the state.